|

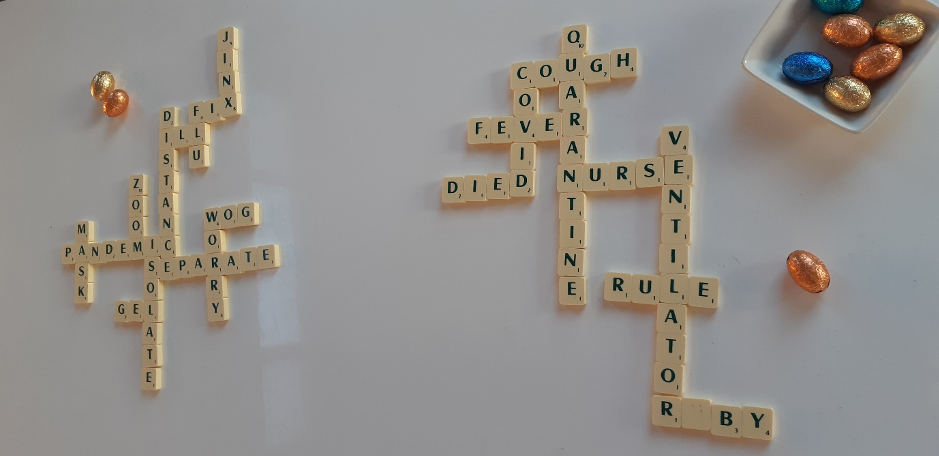

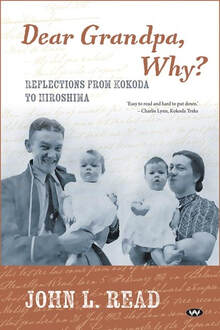

Any notion that we were over-reacting to the Covid19 crisis were quickly dispelled by Thelma Eatts, one of the nonagenarians responding to my questions from the first post in this series. Thelma had to leave school as a young teenager to work on the family farm when her brother went to war and she started nursing at the height of the Polio epidemic, after her sister had already contracted the terrible disease. Yet Thelma reckons the Covid19 pandemic is the most ‘drastic issue she can remember’, made worse by today’s increased population and much greater media coverage. But fear was much more profound during the war than today. Whilst retracing the events leading to my Grandfather’s bravery award conferred posthumously after his plane was shot down over Kokoda, I could almost feel the ‘gut-wrenching fear’ that many of our service men and women felt during conflict. Unsurprisingly, that fear, combined with helplessness and deprivations, were profound on home soil too. Patricia Baulderstone watched nearly every man in her street go off to be killed or destroyed by the war. She was more terrified of the war than Covid19 because there was nothing she could do to stop the cruel Germans or Japanese. Unlike the relative ease of self-isolation at home today, Pat recalls demonstrating she could ride home from Unley High within 5 minutes in the event of an air-raid, otherwise she would have been billeted out to one of the families in a big house with air raid blinds closer to school. There was fear in the regional areas too. Margaret Reed, 94, was a teacher at the Terka one teacher school on the Gladstone railway line near Orroroo when a Japanese invasion appeared imminent. Local parents, fearing ‘the enemy’ would use the railway to storm their little town, dug a bunker near the school for the class to hide in. The fear of Polio that was killing and maiming many people in the 1940’s was also a common theme of the respondants. Pat Baulderstone remembers father removed her siblings from school to stay with their grandparents to avoid infection after a well-known doctor's whole family contracted Polio. Her teachers were unimpressed, yet the schools all closed the next day. However, Merle Tynan, now 97, whose sister contracted Polio and had died by Christmas 1946 leaving behind young children, remembers a twist in the Polio response that may have informed the lack of school closures today. Although schools were closed initially to slow the spread, so many kids went to the picture theatre where they were more likely to be infected, the schools rapidly reopened, with strict rules ensuring kids outside regularly for fresh air. My nonagenarian advisors have suggested we ‘play Monopoly or Scrabble’ to alleviate boredom at home over school holidays, so my ten year old daughter Jarrah and I had a game of ‘Take 2 Speed Scrabble’ with a Covid-19 theme Despite the ration tickets, several nonagenarians recalled food shortages weren’t much of an issue because most was home produced. Celia Fleming even attributed her healthy teeth to the dietary restrictions. Maureen Trutwin however grew up in the city and remembers her father, who owned a grocery store in WA, being “hounded” by customers hoping to sneak some extra tea or sugar rations. Ken McEwin also recalls an undercover “black market” in ration tickets, including he and his 3 brothers ‘donating’ their clothing vouchers to his sister so she could buy her wedding dress. Toilet paper was definitely not a needed or vaunted grocery item for anyone I spoke to. Maureen Trutwin’s frugal mother, who had grown up in the depression, insisted that their household exclusively used second hand paper in the toilet. Old newspaper was most commonly used but when green waxy paper from wrapping up apples was used, she had to be careful to select the non-shiny side for best efficiency. Margaret Reed also used newspaper before and during the war, and like many of us shook her head at the toilet paper stockpiling, which heralded the start of the Covid19 repercussions and identified as the most valued commodity for some in our generation. Arthur Tynan, born in 1923, informed me that although I had presumed our state borders had never closed, interstate travel was also banned during the war when all the trains were commandeered for troop movements or other war efforts. Workers in industries useful in war times were not permitted to leave or change their jobs without a permit and women were called into manufacturing and farming roles. But his wife Merle explained the opposite occurred after the war. Women had to leave work as soon as they were married to allow returned servicemen to work. Due to building material shortages they were not allowed to build a small house (1250 sq foot) unless they had two children. Fathers often helped by making clay bricks. Merle said that she was lucky because her parents allowed her young family a room to themselves, apparently a luxury. If a family had three children they were permitted to build a slightly larger 1400 sq foot house. Little did I know that government restrictions were partly responsible for the baby boomers! Building restrictions and other deprivations continued long after the war as the economy slowly recovered. Ken McEwin remembers that it wasn’t until the 1950s that anyone other than a publican could afford a bottle of beer and forecast it would be many years before the economy would recover from the current crisis. None of my nonagenarian respondents could recall rousing speeches or decisive leadership informing or instructing them of new regulations. They reminded me that there was far less media back in the 1940s but also less need for politicians and other leaders to justify or explain new rules. Rations etc were just accepted. Margaret Reed remembers school kids bringing iron or steel implements from home to be recycled for the ‘war effort’ and many people knitting, writing or cooking for soldiers. However, when announcements needed to be made the mail system was incredibly efficient. Arthur Tynan received his conscription letter within a week or so of Australia declaring war on Japan in December 1942. There were two mail deliveries a day and even overnight deliveries between most capital cities. Imagine how Amazon would benefit from such efficiency today! The oldies were eager to convey tacit advice to our generation in this tough time, similar to the mentoring they received from their parents whose lives were shaped by World War I and the Depression. Today, like back then, everyone needs to “make do the best we can”. There should be “no ifs and buts” about compliance in tough times, “everyone knows what they need to do”. In a striking parallel to my epiphany when researching my grandfather’s life and death in Dear Grandpa Why? my nonagenarian informants expressed a hope that younger generations would benefit from the Covid19 experience by reflecting on, and valuing, our freedoms and opportunities.

Their stories reinforce that awareness, independence, resilience and willingness to adapt come best from experience rather than instruction. I’m keen to learn which experiences from the current ‘lockdown’ are most profound for you and which may leave lasting benefits to yourself and our society. So my questions to anyone under 90 this week are:

decisions and leadership based on expert advice have merit?, home schooling and working brings mixed blessings?)

Stay tuned and respond here or please contribute on johnreadthepragmaticecologist Facebook site.

5 Comments

Sara Weston

19/4/2020 08:10:22 am

I miss seeing my "extended" family - sister, brother-in-law, niece, nephew.

Reply

Trutwin family

20/4/2020 07:45:51 pm

Reply

Natalie Kartinyeri

9/7/2021 02:57:01 pm

Hi

Reply

John Llewellyn Read

25/7/2021 03:08:54 pm

Hi Natalie

Reply

Leave a Reply. |

Details

John L. Read, PhD, author-ecologistWakefield Press, Dear Grandpa, Why? Reflections From Kokoda to Hiroshima Archives

March 2023

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed