Many feral cat trappers are adamant that Kentucky Fried Chicken is irresistible to cats. I’ve often thought KFC is merely a convenient excuse to visit the den of cholesterol before a gruelling trapping trip. But the Finger Lickin’ allure of the Colonel’s secret herbs and spices has now entered textbooks and webpages on cat trapping. However, as I am proudly free from the spell of any fast food fad, I feel compelled to inform you about a superior cat bait that relegates KFC to ‘brussel sprout’ status. Here’s the story of how our group of South Australian ecologists discovered what really makes cats drool. My first tantalising glimpse of a native plains mouse was whilst spotlighting for rare mammals with the Dept for Environment ecologist Helen Owens, near Dalhousie Springs in 1990. At the time we felt very privileged to have seen the largest of the Australian desert mice, which was seemingly destined to join other similar species in being driven to extinction. Over the next decade I saw them again several times where Helen, along with Rob Brandle and Katherine Moseby, monitored these endangered mice at the only two remote desert plains where they could be reliably found anywhere in the world. Then, while searching for the elusive inland taipan on the Moon Plain near Coober Pedy, Katherine and I discovered another population of plains mice. All three localities exemplified the cute rodent’s name, they were expansive treeless plains, indeed largely devoid of any permanent vegetation. With the exception of the occasional patrolling dingo, you had more chance of seeing Mad Max or Priscilla out there than any mammal larger than a plains mouse. We assumed that treeless plains were somehow integral to plains mouse survival – but we were wrong. Fast forward to the new millennium and we no longer had to pack swags, eskies and spare jerrys to head out to find plains mice. They came to us. Plains mice spread hundreds of kilometres from their last remaining refuges and turned up en masse at Roxby, Coober Pedy and even the northern Flinders Ranges. It was an extraordinary resurgence, precipitated by the decline of feral cats and foxes after rabbits, their main prey in many deserts, were all but wiped out by calicivirus. Plains mice found their way into the Arid Recovery Reserve at Roxby, mixing with reintroduced bilbies and bettongs for the first time in over a century. Before long they became the most abundant mammal in the Reserve, in constant danger of being skittled as we drove slowly at night looking for their rarer, reintroduced mates. And they were not just restricted to barren plains. We found their holes and runways all over dunes, through mulga woodlands and on saltbush flats. Their resurgence explained historic records from the well vegetated Flinders Ranges and Eyre Peninsula, where the vegetation is vastly different to their last stronghold in the open desert plains. KFC John! Get back on track! Whilst we were astounded by the plains mouse resurgence on dunes at Arid Recovery, a group of us was also religiously dissecting every feral cat that was shot or trapped in the region. Kelli-Jo Kovac, Hugh McGregor, Katherine and I dissected 2,293 cats over 27 years, an odorous privilege on a scale that no other Australian scientists have matched. To work out what animals cats preferred to hunt, we compared the 3,234 animal remains we found in cat’s guts with over 70,000 animal records we had accumulated from the region. You’ve probably already guessed. The number one animal selected by feral cats was the plains mouse: 50g of rodent flesh packaged up in a cute furry parcel. This reinforced our observations of cats patrolling the boundary of the Arid Recovery Reserve, feasting on the smorgasbord of plains and hopping mice spilling through the cat-proof fence. Most cats preferred catching plains mice to any bait, even greasy portions from a red and white bucket. It dawned on us that plains mice didn’t particularly like barren plains, but they were the only place these furred ice-creams could persist where rabbits were scarce and dingoes kept feral cats at bay. We now had a chance to see if plains mice could also re-establish in other parts of their former range where cats were eliminated. Thirty years ago I would have scoffed at an attempt to reintroduce them to mallee woodlands and spinifex dunes on the Eyre Peninsula, but we are now trying just that in our Mallee Refuge exclosure at Secret Rocks. In early May we moved 50 plains mice, all readily captured within a couple of hours in just one small section of the Arid Recovery Reserve. Some were ‘soft released’ into pens with food and shelter, and 19 were fitted with tiny radio collars to help us track their survival and movements for their first 6 weeks. Would they dig deep enough holes to escape the cold? Would they find enough food and avoid the owls? Could they compete with the larger Mitchell’s hopping mouse? Would they run out through the fence and be gobbled by cats? Every day we learn a little more about whether these endearing and very tasty rodents might survive, maybe even thrive, in such a different environment to where they have lived for over a century. It’s way too early to even guess the answer but we know, by removing cats and foxes, we’ve given them a chance.

6 Comments

Treecreeper Nightmares

Mighty red kangaroos, Macropus rufus, are named for their colouration that matches desert sands. So too is the rufous treecreeper. Although their earthy colours are supremely camouflaged against the iron-stained mallee soils, the orange hue of a rufous treecreeper glows like a beacon when illuminated by a patch of sun. Small, loose flocks of these alluring birds keep in touch with a staccato ‘peep’, delivered slightly higher and more urgently than the microwave-like ‘beep’ of the spotted pardalote. Their penetrating calls can even be heard over the footy commentary when driving at 80km/hr. They demand attention and I rarely resist the urge to stop and watch out for these busy birds, gliding between mallees on barred wings. Unlike the equally appealing sitellas that work for insects as they jump down tree trunks, treecreepers purposefully hop up old mallee trunks, probing for bugs or spiders under the bark. Treecreepers typically nest in a golf-ball-sized hole in an old mallee, which they silently dart into. Too small for cats or goannas, these portals provide security from most predators. However, I have a sneaking suspicion that rufous treecreeper folklore recalls a fearsome marauder that was once their greatest nemesis. “Keep quiet so Ngintingkaparrtjilaralpa doesn’t find us”, the treecreepers may have warned their noisy nestlings as soon as the sun sets. A century ago, an agile marsupial predator occupied the entire range of the rufous treecreeper from southern Western Australia to Eyre Peninsula. Active at night when the treecreepers were roosting, the carrot-sized red-tailed phascogale once leapt through the mallee canopy, brush-tipped tail trailing behind like a rudder. With males living less than 12 months and having to consume 30% of their body weight every day to satisfy their turbo-charged metabolism, phascogales were incessant, voracious hunters. Any animal weighing less than them, including nestling treecreepers, were fair game. The Secret Rocks treecreepers were enjoying the best season for over a decade following record rains last January. Nesting pigeons, little eagles, babblers and honeyeaters also flushed wherever I walked. This was the season the birds needed to bounce back from the drought, heatwaves and fires of 2018-19. Treecreeper calls once again rang out in the Mallee Refuge exclosure, where the goats, rabbits, roos, cats and foxes had been removed. But I wasn’t birdwatching, I was witnessing a drama unfolding in a dense tea-tree from which the ping of a radio-collar was emanating. We had recently released the first phascogales on Eyre Peninsula for more than 100 generations. No-one had radio-tracked immature phascogales in a new environment and we were anxious to learn if the zoo-bred animals knew how to hunt in the wild and would remain in our sanctuary. Concerned that they would not be able to forage long enough over the unseasonably cold nights, we provided them with boiled eggs, roo mince and mealworms near their nestboxes, expertly crafted by the Cleve and Kimba Men’s sheds. But like any ravenous and inquisitive teenagers, our young charges ventured away from the safety of their boxes. With a thermal scope I watched spellbound as these arboreal gymnasts darted through the foliage of bushes and scurried well above my head-hight up the same tree trunks that rufous treecreepers foraged on by day. Although they are spunky, endangered and a national priority for reintroductions, I worried that our new phascogales may, in turn, endanger the treecreepers. As I was pondering the potential repercussions of reintroducing these spectacular little hunters, a repetitive pigeon-like cooing started up in the blackness of the mallee night. The bright object glowing in my thermal scope temporarily paused its frenetic activity, perhaps innately recognising the call of the tawny frogmouth that could swallow it in one gulp. I too was nervous. Although we had removed cats and foxes, we couldn’t protect our naïve little marsupials from birds of prey. Scrrreeeeeeeech! My heart raced; then dropped. A Barn owl had just completed the quinella of our new predator’s predators! Ensconced in her hollow, I can imagine Mrs Treecreeper comforting her brood. The owl’s curdling screech that strikes fear into small nocturnal mammals is comforting for diurnal, or day active, birds. Her brood will be safe tonight with the owl or frogmouth sure to pick off any Ngintingkaparrtjilaralpa naïve enough to venture up the unprotected trunk to her hollow. We will watch, worry, wonder, hope and dream. Wonder if enough phascogales can survive predators and misadventure and again establish on Eyre Peninsula. Hope that owls, goannas and maybe even carpet pythons will keep phascogale numbers in check through countless more Mallee Thrillers, so the treecreepers can keep ‘peeping’ in the mallee. And dream that farmers will also embrace and benefit from phascogales picking off locusts and mice in remnant scrub, like hyperactive little pest controllers.  Malleefowl Valentine? I inched forwards on my belly, commando-style, until I reached the edge of the four-metre-wide mound. Craning my neck upwards, I received a face full of grit as ‘The Dude’ busily flicked sand and sticks from the top of his mound. The Dude was no ordinary malleefowl. I’d first encountered him six months earlier when we were surveying about three hundred local mounds around Secret Rocks. For nearly a decade, the active mound counts had been declining, and we rarely even glimpsed a bird. But today I had heard The Dude before I saw his freshly scraped nest. Unlike any other malleefowl I had encountered, he didn’t seem at all phased. Whilst I measured and photographed his nest for the National records, he strutted around like a cocky rooster and quickly returned to renovating his mound soon after I left. Because he was one of the few malleefowl we still knew of in the district, Katherine and I were keen to radiotrack The Dude. Other tracked malleefowl had been killed by cats or foxes. Some started up new mounds every couple of years and their movements revealed the importance of different habitats for these threatened birds. Our co-worker Cat and I were now attempting to catch him with hand-nets when he kicked sand in my face. Whilst lying down waiting for The Dude to walk within range of my net, I noticed a clear glob on the mound. A malleefowl moves many kilograms of dirt every day on and off their mound to maintain buried eggs at the optimal temperature, or to open the nesting cavity for a visiting female. This clean glob had therefore presumably been just deposited by The Dude. I was trying to figure out whether it was animal, vegetable or mineral when Cat picked it up and proceeded to squish some tiny seeds out of the grape-sized jelly. Intrigued, I tentatively tasted the morsel, still not knowing from which end of The Dude it had originated. Oh my goodness! Only a sprinkling of cinnamon could have enhanced the sweet apple flavour. With the exception of honey ants dug by industrious Anangu women in the APY Lands, this was the sweetest bushfood I’d ever sampled. Cat and I reckoned the Dude had found an apple berry, even though neither of us had ever seen one at Secret Rocks. Fast forward to this week, and we were again surveying our malleefowl mounds. The Dude’s mound was inactive this season, but only a few hundred metres away I’m confident I met him again, proudly scratching away on a new mound, unperturbed by my presence. Next, I found my first ever apple berry plant, a twining vine with distinctive mauve flowers. Coincidentally, maybe, the apple berry vine was growing only a few metres from an old malleefowl mound. Purple-flowered twining Appleberry vine Last night, Cat was almost as excited at her own discovery of an apple berry as she was at finding more active malleefowl mounds. Cat’s apple berry had actually been growing on an old mound. I had found another, again growing near a mound that I was checking. Clearly the great rains this year had helped germinate these normally rare plants, but when I wander, I wonder. I couldn’t help speculating that the malleefowl played a role too. Anyone who has watched a David Attenborough doco, or observed wild bowerbirds, will understand the extraordinary behaviours some male birds use to attract a mate. The Dude had spent many months digging out, lining with mulch, and then mounding up his massive nest, in the hope that a hen would reward his diligence. Could the fruit have been a Valentine offering? Or maybe evolution had selected birds that ‘planted’ prized fruits near their nest for themselves, their mates or even their precocious young who apparently don’t receive any parental assistance. Provisioning of nest mounds with treats has not been recorded or even suspected despite hundreds of hours of watching malleefowl directly or via cameras. But just maybe malleefowl can add dispersal of important food plants to their repertoire of ‘ecosystem services’. In Western Australia, malleefowl scoff on poison pea seeds, immune to their toxin. But cats or foxes that eat these toxic malleefowl are killed; the unfortunate birds helping protect other wildlife from these invasive predators that have not evolved tolerance to the native poison. At Secret Rocks I have twice seen where fires have been stopped by the raked clean margins of active malleefowl mounds, leaving an unburnt downwind ellipse of remnant refuge habitat for plants and wildlife. Like many other animals that are disappearing from our bush, the decline of malleefowl is precipitating a range of repercussions, many that we are blissfully unaware of. Every time I watch wildlife like the Dude, taste a surprising morsel, or let my imagination run wild with ecological theories, I am increasingly committed to helping nature’s amazing network of interactions thrive. 3 September, 2022

I wish all Dads could… have the type of afternoon I just enjoyed with my 12 year old daughter. I’d promised Jarrah we would go looking for one of Australia’s rarest and cutest mammals. Whilst waiting for the fog to lift we’d moved a Felixer to target a feral cat spotted on a camera outside our cat-proof fence. For, unlike any of our other rare marsupials, the sun had to poke through the low cloud before numbats emerge. A few weeks ago our workmate Cat Lynch had picked up three numbats flown over from Perth. These were old numbats, surplus to the Perth Zoo’s needs, like green-collared greyhounds or ex-racehorses needing a back paddock to retire. We were happy to oblige. These retirees allowed Katherine and Cat to trial special new adjustable radiocollars, prior to a larger numbat reintroduction planned for later this year. They also let us assess whether the country rehabilitating rapidly from the big fires two and a half years ago would be suitable. The platypus is often joked about as being concocted by committee, but the numbat must vie for the title of Australia’s most bizarre mammal. Their tail could be grafted from a squirrel, their rump is adorned with exquisite zebra-like white bands and their tongue is turbo-charged and echidna-like. And, fortunately for numbat watchers, they only come out when its warm and sunny, like thorny devils. Although each evening we confirmed they had found safe shelters, we had deliberately not checked on our new numbats for the first few weeks. Until they had found plenty of hollow logs to hide in, we were worried that they could be picked off by falcons or goshawks if they ran blindly away from us. The ever louder beeps of our radiotracker led us to hollow logs under really old mallees. Jarrah and I stopped and looked, knowing our quarry was less than twenty metres away. And we waited and watched. Then Jarrah spotted it. Frozen motionless by the logs, we were amazed that the boldly banded, orange beast with a flamboyant fluffy tail could hide. Then, as if deciding we represented no threat, Saul (that’s the name he came with) showed his tricks. Standing high on his back legs like a meercat, Saul checked us out. With tail held aloft he then walked, long-legged but soft-footed, to a log, jumping up to show off in the sun. From his elevated perch Saul obviously saw something he liked and meandered off, sniffing at sticks as he walked. I was watching through binoculars and only noticed how close he had come to Jarrah when she came into view. Motionless, and transfixed by the action she was observing through her new phone, I watched Jarrah’s concentration dissolve into a broad grin when Saul nosily slurped at termites under a barky stick in front of her. We had agreed not to follow the numbats as they moved off. As I noted Saul’s GPS coordinates on our datasheet, Jarrah skipped over and gave me a high five. “Fully sick” she exclaimed, although I’d made no such diagnosis. I’m not sure whether I was more delighted at her reaction or my first close-up experience with a wild numbat. Now restricted to a small pocket of south-west Western Australia and a handful of fenced safehavens, numbats had not delighted anyone on Eyre Peninsula for over a century. And I got to share the experience with Jaz. Now engaged and engrossed, heading off to find the other numbats, we discussed how dependent they are on the special conditions we could offer. Only half the size of a rabbit, numbats make little more than a snack for foxes and feral cats that we had fenced out and removed. We walked away from the monster old mallees to an area that must have had a cool burn 60-80 years ago. The dead hollows remaining from that fire now provided shelter for our geriatric numbats, all these years later. The shrubs regenerating after goats had been removed provided them cover from birds of prey. Even the scattering of finger-sized sticks, the sort I had collected for kindling without a thought, seemed to host many of the termites our new friends depended upon. Hopefully Saul and his two mates will be the first of many numbats to eventually thrill kids and parents alike on Eyre Peninsula. Hopefully their endearing looks and behaviour will encourage widespread control of foxes and cats, proactive use of control burns to prevent disastrous wildfires and removal of livestock, goats and even deer and overabundant kangaroos from enough scrub patches to entice more kids away from messaging their friends and playing Subway Surfers, if only for a couple of sunny hours on a weekend.  WUPPA CHUPPA CHUPPA CHUPPA The unmistakable sound of a helicopter banking through the scrub cut through our dawn chorus of white-fronted honeyeaters, scrub robins and crested bellbirds. I scanned the horizon searching the row of shiny new pylons that emerged, offensively, from patches of low-lying fog. But the chopper stringing the new Eyre Peninsula High Voltage transmission line was hidden. To Mecanno enthusiasts and power infrastructure nerds, the towering beacons represented ‘Stairways to Heaven’. But for us as landholders, these taller, shinier pylons were aesthetic and environmental insults, reminiscent of Joni Mitchell’s song about how we ‘Paved Paradise to Put up a Parking Lot’. NIMBY Katherine and I were aware of the ecological risks of carving corridors through native vegetation. We’d seen horehound and onion weed spread along the original powerline and were concerned about buffel grass establishing and irreversibly changing the mallee. I’d followed fox and feral cat tracks along the corridor and even seen one of these foxes kill an endangered Peregrine falcon chick. Trespassers using the powerline access track had shot a wedge-tailed eagle and a malleefowl. Our best fruiting quandong tree had been mulched to smithereens when Electranet’s contactors removed ‘encroaching regrowth’. Like most people passionate about their property or cultural or environmental jewels, we opposed the new powerline traversing our patch. “NIMBY” (Not In My Back Yard!), we declared valiantly but unsuccessfully. The economics of re-routing the powerline along the cleared Lincoln Highway or edges of farming land instead of ripping another line through one of the last strongholds of the nationally threatened sandhill dunnart, malleefowl and chalky wattle didn’t stack up. Not all bad WUPPA CHUPPA CHUPPA CHUPPA. Surprisingly though, I was actually pleased to hear the chopper, one of the very rare anthropogenic noises audible at Secret Rocks. Through using the chopper-stringing technique, Electranet had avoided clearing a new line. Instead they built short spur lines from the existing powerline track to their new megapylons. A couple of weeks ago their environmental staff had taken me to inspect their stringing plans and proposed rehabilitation work. Gangs of High Vis workers in cranes and trucks dutifully pulled over into demarcated passing areas as we passed. Other areas defined by bunting prevented potential damage to environmental or cultural sites. As expected, Electranet had also thoroughly surveyed the powerline corridor for important sites and had arranged offsets for unavoidable damage to vegetation or threatened species habitat. I’d also been impressed with how their principal contractor, Downers, had arranged the prefabricated pylon segments on the carefully demarcated pads like a Tetris, keeping disturbance to a minimum. But just because they were doing a good job minimising their impacts didn’t mean that Electranet deserves an environmental award, yet. Bunnies or bilbies? Twenty years ago, whilst working as an ecologist at Roxby, I had been encouraged to answer a provocative question “Are miners the bunnies or bilbies of the rangelands?” Before myxo and then calicivirus decimated their numbers, rabbits were environmental enemy #1 in Australian deserts. By contrast the rare bilby, was a conservation icon and an important ‘ecosystem engineer’ that helped the environment. However, in some important ways rabbits had replaced the digging role that bettongs and bandicoots once played. Likewise, the powerline track created firebreaks, breaking up the country and helping to reduce large scale wildfires. This is something that the Barngala used to do more efficiently and expertly to refresh the country using patch burning. Several important ‘islands’ of unburnt scrub were saved by the powerline track during our Christmas 2019 fires. Ironically one of the rare plants Electranet was required to survey for actually benefited from the powerline. Swainsona pyrophilla means ‘fire loving’ but it also loves bulldozers. Although not found on the preconstruction surveys, several plants flowered spectacularly on the pylon pads after the big January rains and their seeds will sit dormant for decades until the next fire or bulldozer stimulates germination. Just as an underground mine was not the main threat to the desert environment around Roxby, the powerline construction alone is unlikely to be in the top ten threats to mallee animals or plants. Unnaturally large and severe fires, too many feral or native herbivores, weeds, invasive foxes and cats, climate change and possibly chemical spray drift from neighbouring farms may all represent greater long-term threats than a sensitively-constructed powerline. Strive for Positives Whilst the expectation and requirements on developers is to minimise their disturbance, they have an opportunity to leave a positive legacy by helping to address more significant threats. Two decades ago I argued (at that time) that Western Mining acted like bilbies by leaving a net positive environmental legacy through their control of regional pests and supporting research that benefited the environment well beyond their minesite. Electranet could have, and still might, plant other disturbance-liking rare plants under their pylons. They could take advantage of their resources to leave other positive legacies. ‘Bean counters’ with short-term budgetary concerns may protest at slightly more expenses, but visionary leadership will reap rewards and maybe awards. Our transition to renewable energy will require more powerlines. Some will traverse wild and beautiful places with endangered plants and animals. Again the NIMBY cry will be heard. But would-be opponents will be far less vociferous and demanding of companies with a track record of exceeding compliance and delivering benefits to regional environments and cultures. The challenge of electricity producers, distributors and retailers is to convince us how ‘green’ their power really is.

Sharing The Secret Part 2

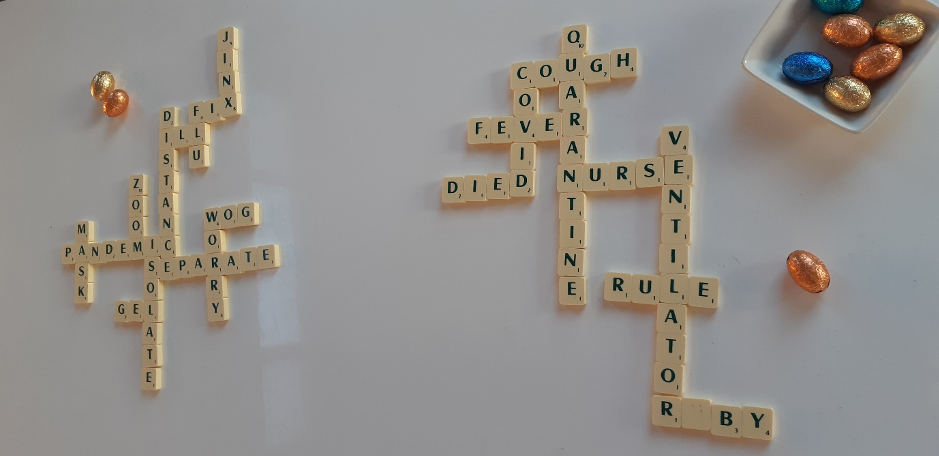

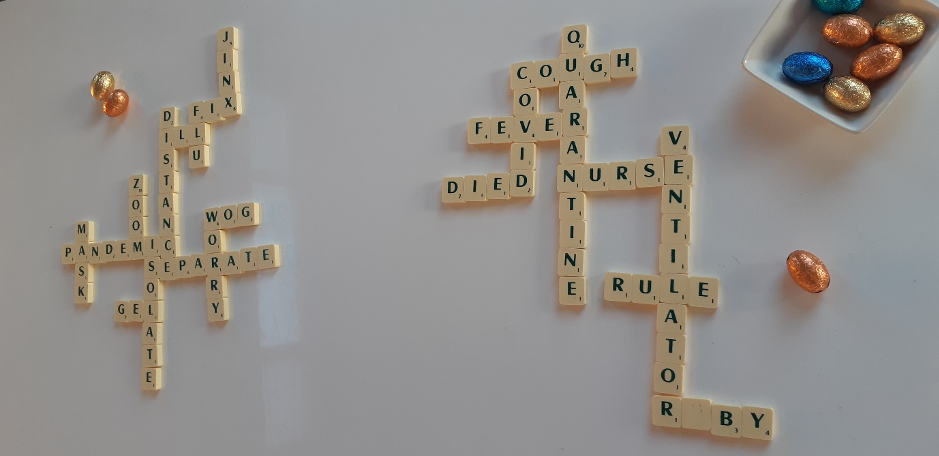

Blind-sided Out at the Waddikee Tennis Club, the Friday night stories about skiing and kayaking exploits on flood-filled lakes turned biological. “John you might know…. we saw all these worm things that weren’t worms floating on the edge of the Possum Flat lake”. A quick google search confirmed my guess. Dylan and Chloe had seen blind snakes. “What you mean they are snakes …. and they are blind?” No one clustering around the phone image had heard of blind snakes, let alone seen one. Buts that’s no surprise. Although there are around 50 different species, most are seldom seen. These worm-thin, silver-pink snakes seldom grow longer than a school ruler, and never as thick as a drinking straw. They mostly live underground, which is why they are blind. They have a tiny forked tongue to prove they’re a snake and a pointy tail that would struggle to impale a marshmallow. Blind snakes eat the eggs and larvae of ants and termites. Their scales are so tiny and smooth that ants can’t bite or sting them. Sometimes they are seen on the ground on warm nights, especially after rain, but I’ve seen way more blind snakes in the stomachs of feral cats than anywhere else. I’m hoping that one day I will discover a new species, gift-wrapped in tabby fur. Like many other small and nearly limbless skinks and legless lizards, blind snakes often live in deep leaf litter that accumulates in dry swamps. These are the richest and dampest areas and usually hence the ideal place for many small reptiles. But when flooding rains arrive, this eutopia instantly changes into an inhospitable lake, and many thousands drown. Some are even noticed by passing kayakers. Floods, like fires and cat guts provide amazing opportunities to find animals that are normally elusive. My most memorable flood-find was a marsupial mole that had drowned when a cyclone flooded the Great Sandy Desert inland of Port Hedland. This bristle-furred golden carcass could fit in the palm of my hand and remains the only mole I have seen in the flesh, despite knowing I have walked over them many times. We’re going on a mole hunt Marsupial moles are even harder to find than blind snakes, and, from the response at Waddikee, are just as poorly known. They are thought to only come to the surface if the sand is saturated, or if they are sick. Think about that for a second. Aboriginal informants and awestruck biologists believe marsupial moles eat, find each other, mate, give birth and suckle their young (in a backwards facing pouch so it doesn’t fill with sand) all in the sand up to a couple of metres deep. Foxes are good at hearing and digging up moles. At some sites up to a third of fox scats have distinctive mole hair in them. Rarely their squiggly tracks can be seen on sand before they dive underground again. I’ve spent a couple of weeks out in the desert listening to their distinctive scratching noises with special geophones, metal disks spread out over the ground that enable us to pinpoint where they are and guess what they are doing. But by far the best way to find evidence of marsupial moles is to dig a grave-sized trench on the crest of a sandhill. After a day or so to dry out, the smoothed down sides of these trenches may reveal the near circular shape where torpedo-shaped moles have ‘swum’ through the sand. If the mole has been there recently, the uncompressed sand spills freely out of the hole, but older holes are only marked by a faint trace. Digging mole trenches had enabled us to confirm that moles are more widespread than previously thought. I’d found them in the Great Victoria Desert near Maralinga, in very similar country to Secret Rocks. Indeed, the Pinkawillinie dunes and those stretching from Lake Gilles all the way to the Munyeroo coast near Cowell are essentially the extension of the Great Victoria Desert. Could moles live here too? The January floods created a perfect mega mole trench when the biggest flood since the land had been cleared cut through dunes vegetated by centuries old native pines right next to Pinkawillinie Conservation Park. The resulting 3-5 metre sand cliff, stretching 100’s of metres, provided a far easier way of checking for mole holes than digging trenches with a shovel! While others were assessing the damage to fences and paddocks, or skiing in newly-formed lakes, I rubbed down the sand-cliffs, searching for the tell-tale signs of moles. I found none in the dunes in mainly cropping land and, unfortunately for me, none of the massive dunes in the park had been cut by the floodwaters. It is probably unlikely that moles have joined other rare animals like sandhill dunnarts and malleefowl that spread from the Great Victoria Desert to the more isolated dunes of the Kimba district, but if you don’t look you won’t find. Photo to follow next week, below.  Remember January 22, 2022? Today was one of those dates I’ll remember for life. The Bureau had been talking up a big rain so last night I rushed home from the beach. Katherine and I had just completed an 18-kilometre addition to our feral proof Mallee Refuge fence at Secret Rocks, between Kimba and Whyalla. The tiny bandicoots reintroduced in July were raising their second cohort of twin joeys. Last week we caught an endangered sandhill dunnart and thrilled at the return of a pair of malleefowl. One cat or fox squeezing under where water had rushed, or worse still sauntering in if the fence had been knocked down, could quickly finish them all off. Pelting rain on our iron roof snapped me awake at 4:10. The energy was contagious. I jumped into my bathers, donned a headtorch and ran outside. Through the torchlit rain curtain I could see water, the most precious asset in the bush, gushing out the top of our house tank. Between lightning strikes I scooped leaves and silt from the filter basket and was rewarded by the hollow sound of a tank rapidly filling. There was already 65mm in the gauge. Surprise Creek As soon as the feeble daylight had breached the cloud ceiling, I went out exploring. To my surprise a 40m wide creek was flowing across our driveway in a series of rapids. We’d lived here for 12 years and never even suspected this was a creek, only 500 metres from our house. I was intrigued. Did this flow just get absorbed by the sandplain or did it end in a swamp? Boosted by tributaries from ‘Beer Rock’ and other local outcrops, the creek became wider rather than disappearing into the sand as I had suspected. Fortunately, the flow had spread and filtered through our new fence without any damage. Wherever I cleared debris from the netting, a gush of dammed back muddy water surged on downstream. Relieved that ‘Surprise Creek’ hadn’t knocked the fence down I continued to follow it, paying more attention to the bush. The birds were also excited by the unexpected torrent. Rainbow bee-eaters, that had been surprisingly scarce this summer, noisily snapped up flying insects. Budgies and masked woodswallows, the most excitable of desert birds, wheelied around in noisy flocks. Spending my 20’s and 30’s in the desert at Roxby I always loved it when these desert nomads paid a visit. They had found the creek before me. All the way from the house the creek had been flowing through mallee burnt in our big fires two summers ago. But now the creek demarked the boundary of unburnt scrub. Further along the creek marked the edge of a 2km long control burnt I lit nine years ago. I’d been intrigued by bushfire patterns since my first brief contract after Uni mapping fire scars in National Parks. Fire edges could often be explained by wind changes, and sometimes changes in vegetation. Previous floods of Surprise Creek had washed fallen combustible leaves from a wide strip of mallee, way more effectively than a dozen rake hoes or even the fancy new backpack leaf blowers we used to slow down our 2019 fire. The trilling rattle of burrowing Neobatrachus frogs indicated I was approaching the terminal swamp, where a dune blocked Surprise Creek. I’d studied these turbocharged frogs at Roxby. When water from big rains percolated down to their cocoon of shed skin, the frogs scramble up through the mud, eat their old skin and embark on a few days of frenetic action. Females rapidly develop their clutch of eggs as they seek out the best calling male in the deepest pond. Lucky males, and sometimes some cheeky interlopers, grasp the slippery females with special glove-like nuptial pads and fertilise their string of eggs. The race continues as the tadpoles hatch and grow faster than any other tadpole in the world so they can metamorphose and bury themselves before their pond dries out. Seventeen days was the record in shallow hot ponds but taddies in deep cooler ponds could take over 9 months. What about Secret Rocks fence? If Surprise Creek had flowed so vigorously, I worried what damage had been caused to our fence where it crossed known drains. Secret Rocks, the iconic granite outcrop where Edward John Eyre was introduced to a reliable water source in 1840, was my main concern. That was where the bandicoots were, and I knew of three places where smaller rains had run water off the rock and through the fence. I jogged through the mud back home, through another brief but intense storm. The deluge, or maybe the flooding of the trench where our internet connection runs, had shut down the internet - no BOM weather radar or even Facebook updates from neighbours. I strapped a long-handled spade to my pushbike and headed off to check the 25km perimeter fence. Within 10 minutes of boggy riding my back tyre was flat. Worried about the bandicoots I ditched the bike and headed off on foot with my spade. Amazingly, the first drain I reached near Secret Rocks had not even flowed to the fence, the same with the second. This highest risk part of our fence seemed to have been spared the heaviest rain. More frogs Trilling frogs that have been sought by local kids for generations were already amplexing in the rockholes. I counted 8 in one, 14 in another. My phone beeped with messages and I quickly learned that some mates near Kimba had received 220mm, others over 300mm, of rain - nearly three times what I had emptied from my rain gauge at home. Apparently there was more on the way. With another 16km of fence to check I slipped back down the rock, taking the opportunity to slide down a mossy waterfall and past some rare acacias from the Botanic Gardens we planted last year. It had not rained for a few hours by now and the humidity was stifling, my bathers now wetter from sweat than rain. A couple of hours later I came across a lake straddling our new fence, flooding dense mallee on both sides and ruling out driving around this section of fence for weeks. This was the fifth site I found breeding frogs. Not having had a drink all day, I knelt down and sucked up eucalyptus-flavoured water, very different from the familiar rainwater flavour of rockholes or claypans. Ironically, as soon as I’d had a drink I heard a distant roar, like the Perth-bound jets that flew over before COVID. But there were no planes in the sky, only a black cloud eerily bruised with green and purple. The birds that had been noisily feeding on flying ants and termites went quiet. From ahead a waterfall approached, roaring until it reached me. Suddenly the tracks along both sides of the fence turned to rushing torrents, racing toward the lake I had just drunk from. Then the lightning started. I’d been cracked by lightning before and didn’t fancy repeating the experience walking underneath the floppy overhang of a 2-metre netting metal fence. As I jogged for home I noticed one of my cat-killing Felixers in danger of being flooded. I’d not even considered the likelihood of flooding when I chose this spot where I had seen feral cat tracks. I wasn’t the first to misread floods. The old Roxby Downs Homestead was nestled amongst the gums and tea trees of Chances Swamp, an ideal location until it was flooded to the top of the door several times, including in 1989 and 2007 when I was there. I wondered how many inappropriately located silobags, sheds or houses on the EP were also inundated or threatened by these unprecedented floodwaters. Home came into sight as the dark afternoon faded into twilight. None of the fence was down, at least until the last deluge, which was testament to savvy fence alignment designed to avoid dunes, rocks and known drainage lines. Our workmate Cat Lynch was also relieved as my responded to all her worried messages. Centuries-old sandalwoods and pines near our house that survived the 2018-19 drought were already rejoicing, their roots probably drenched for the first time in decades. Another 36mm in the gauge brought our total to 110mm for the day. Pikey on the radio announced his rainfall tally had smashed generational daily records just down the Cowell Road. Footsore on my couch, I giggled. Would Pikey and Rachel change the name of their farm from ‘Winter Springs’ to ‘Summer Torrent’? This unusual almost stationary tropical low had delivered a rain for the ages. What’s next? The thunder and pelting rain had stopped for now but there was something eerily quiet about the calm after the storm. Then it dawned. There were no giant rain moths bashing into our widows like flat tennis balls. I hadn’t noticed any of their tell-tale cases where they typically emerged from the ground after a big rain. Why were the dragonflies already here but the rain moths hadn’t made an appearance? From studying the aftermath of floods in deserts I expected a series of plagues to follow a big rain like this; flies, grasshoppers, caterpillars, stink beetles, moths, mice and maybe even nomadic kites and owls. I was intrigued to learn how the mallee would respond. When would the rain moths or the lumbering bright orange jewel beetles emerge? How many of our new swamps would last long enough for tadpoles to metamorphose? I set myself a challenge of documenting the changes for a year, a year when we hoped to reintroduce more rare animals and threatened plants to this special drenched place. Any notion that we were over-reacting to the Covid19 crisis were quickly dispelled by Thelma Eatts, one of the nonagenarians responding to my questions from the first post in this series. Thelma had to leave school as a young teenager to work on the family farm when her brother went to war and she started nursing at the height of the Polio epidemic, after her sister had already contracted the terrible disease. Yet Thelma reckons the Covid19 pandemic is the most ‘drastic issue she can remember’, made worse by today’s increased population and much greater media coverage. But fear was much more profound during the war than today. Whilst retracing the events leading to my Grandfather’s bravery award conferred posthumously after his plane was shot down over Kokoda, I could almost feel the ‘gut-wrenching fear’ that many of our service men and women felt during conflict. Unsurprisingly, that fear, combined with helplessness and deprivations, were profound on home soil too. Patricia Baulderstone watched nearly every man in her street go off to be killed or destroyed by the war. She was more terrified of the war than Covid19 because there was nothing she could do to stop the cruel Germans or Japanese. Unlike the relative ease of self-isolation at home today, Pat recalls demonstrating she could ride home from Unley High within 5 minutes in the event of an air-raid, otherwise she would have been billeted out to one of the families in a big house with air raid blinds closer to school. There was fear in the regional areas too. Margaret Reed, 94, was a teacher at the Terka one teacher school on the Gladstone railway line near Orroroo when a Japanese invasion appeared imminent. Local parents, fearing ‘the enemy’ would use the railway to storm their little town, dug a bunker near the school for the class to hide in. The fear of Polio that was killing and maiming many people in the 1940’s was also a common theme of the respondants. Pat Baulderstone remembers father removed her siblings from school to stay with their grandparents to avoid infection after a well-known doctor's whole family contracted Polio. Her teachers were unimpressed, yet the schools all closed the next day. However, Merle Tynan, now 97, whose sister contracted Polio and had died by Christmas 1946 leaving behind young children, remembers a twist in the Polio response that may have informed the lack of school closures today. Although schools were closed initially to slow the spread, so many kids went to the picture theatre where they were more likely to be infected, the schools rapidly reopened, with strict rules ensuring kids outside regularly for fresh air. My nonagenarian advisors have suggested we ‘play Monopoly or Scrabble’ to alleviate boredom at home over school holidays, so my ten year old daughter Jarrah and I had a game of ‘Take 2 Speed Scrabble’ with a Covid-19 theme Despite the ration tickets, several nonagenarians recalled food shortages weren’t much of an issue because most was home produced. Celia Fleming even attributed her healthy teeth to the dietary restrictions. Maureen Trutwin however grew up in the city and remembers her father, who owned a grocery store in WA, being “hounded” by customers hoping to sneak some extra tea or sugar rations. Ken McEwin also recalls an undercover “black market” in ration tickets, including he and his 3 brothers ‘donating’ their clothing vouchers to his sister so she could buy her wedding dress. Toilet paper was definitely not a needed or vaunted grocery item for anyone I spoke to. Maureen Trutwin’s frugal mother, who had grown up in the depression, insisted that their household exclusively used second hand paper in the toilet. Old newspaper was most commonly used but when green waxy paper from wrapping up apples was used, she had to be careful to select the non-shiny side for best efficiency. Margaret Reed also used newspaper before and during the war, and like many of us shook her head at the toilet paper stockpiling, which heralded the start of the Covid19 repercussions and identified as the most valued commodity for some in our generation. Arthur Tynan, born in 1923, informed me that although I had presumed our state borders had never closed, interstate travel was also banned during the war when all the trains were commandeered for troop movements or other war efforts. Workers in industries useful in war times were not permitted to leave or change their jobs without a permit and women were called into manufacturing and farming roles. But his wife Merle explained the opposite occurred after the war. Women had to leave work as soon as they were married to allow returned servicemen to work. Due to building material shortages they were not allowed to build a small house (1250 sq foot) unless they had two children. Fathers often helped by making clay bricks. Merle said that she was lucky because her parents allowed her young family a room to themselves, apparently a luxury. If a family had three children they were permitted to build a slightly larger 1400 sq foot house. Little did I know that government restrictions were partly responsible for the baby boomers! Building restrictions and other deprivations continued long after the war as the economy slowly recovered. Ken McEwin remembers that it wasn’t until the 1950s that anyone other than a publican could afford a bottle of beer and forecast it would be many years before the economy would recover from the current crisis. None of my nonagenarian respondents could recall rousing speeches or decisive leadership informing or instructing them of new regulations. They reminded me that there was far less media back in the 1940s but also less need for politicians and other leaders to justify or explain new rules. Rations etc were just accepted. Margaret Reed remembers school kids bringing iron or steel implements from home to be recycled for the ‘war effort’ and many people knitting, writing or cooking for soldiers. However, when announcements needed to be made the mail system was incredibly efficient. Arthur Tynan received his conscription letter within a week or so of Australia declaring war on Japan in December 1942. There were two mail deliveries a day and even overnight deliveries between most capital cities. Imagine how Amazon would benefit from such efficiency today! The oldies were eager to convey tacit advice to our generation in this tough time, similar to the mentoring they received from their parents whose lives were shaped by World War I and the Depression. Today, like back then, everyone needs to “make do the best we can”. There should be “no ifs and buts” about compliance in tough times, “everyone knows what they need to do”. In a striking parallel to my epiphany when researching my grandfather’s life and death in Dear Grandpa Why? my nonagenarian informants expressed a hope that younger generations would benefit from the Covid19 experience by reflecting on, and valuing, our freedoms and opportunities.

Their stories reinforce that awareness, independence, resilience and willingness to adapt come best from experience rather than instruction. I’m keen to learn which experiences from the current ‘lockdown’ are most profound for you and which may leave lasting benefits to yourself and our society. So my questions to anyone under 90 this week are:

decisions and leadership based on expert advice have merit?, home schooling and working brings mixed blessings?)

Stay tuned and respond here or please contribute on johnreadthepragmaticecologist Facebook site.  We’ve just got to do it, Part 1 Three months ago, like many Australians, I was ensconced in arguably the largest bushfire tragedy the world has ever experienced. Those fires focussed our attention on the safety and wellbeing of our communities and wildlife. We knew they represented the coup de grâce after an insidious and unprecedented hot dry period and we worried what the future held. The term Covid19 and the expressions ‘social distancing’ and ‘self isolation’ had not been coined when I was battling alongside the fire crews, although we knew about a nasty new flu affecting a Chinese province. The New Years’ eve light show at home was very different this year while battling the bushfires Yet Covid19, not our fires, will be remembered as one of the most influential global events for generations. I can recall horrific assassinations, wars, natural disasters and genocides, along with great sporting and cultural achievements. I recall my schoolkid fears about the Cuban Missile Crisis plunging us into a nuclear holocaust which cemented the nuclear disarmament ambitions of my generation. Whilst other tragedies have undoubtedly affected families or even countries more, I doubt whether any crises have affected our global community like Covid19. The September 11 terrorist attack and subsequent wars heralded a new world order, (we still can’t carry water bottle on planes) but Covid19 looks destined to trump even that shocking event. Sporting competitions, artistic events and even the Adelaide Zoo that have remained open for lifetimes have been suspended. National and State borders have been closed and communities and families have been isolate. But two recent changes in my life have really driven home the magnitude of Covid-19. Last week I was unable to hug my 81 year old mother, something that I have always taken for granted and treated as a given. But the Prime Minister’s declaration last week that funerals could not be held with more than 10 mourners was the ultimate wake-up call for me. A local lad killed in a car crash and the inspirational ‘Frog Man’, Mike Tyler, who passed away last week will not receive the goodbyes that they and their families and friends deserve. Mike’s wife, Ella lamented to me “The funeral was simply five family members in a stark room at the funeral parlour. No music and no friends to help us cope. Just an identification form to sign!” The “frog man” Mike Tyler who passed away last week without the funeral he or his family deserved. (image courtesy of Ella Tyler)

Although I have been unsettled and shocked by these new rules, there is one small glimmer of hope. Our Prime Minister prefixed his announcement with the statement “I’m really sorry but we’ve just got to do it”. I can’t recall leaders previously making draconian (or even unpopular) decisions with such serious social and financial implications on the basis of scientific evidence or opinion. In a small way I’m buoyed by their willingness to govern for the long-term benefit of society, of restricting the liberties of one generation for the benefit of another. I wonder where strong leadership could steer (or push!) our society and the role crises have in enabling such change. Whilst we are living through this strange new world of social isolation, I’ve decided to compile a fortnightly blog, to place this event in historic context, to learn from past crises, discuss our current situation and dream about what can be learned for the future. This week I am reaching out to nonagenarians, yes that’s right, those aged 90 or thereabouts, who recall the grief, fears and depravations of WWII and its aftermath. I’m asking how Covid19 compares to the 1940s and how they coped back then and what they learned from the experience? In case you aren’t 90, or haven’t got a parent or neighbour you can quiz, your opportunity will come in following weeks when I explore our current fears and frustrations, how different leaders (national, state, local or sporting) are approaching the crisis and how we can learn from this unprecedented experience. Stay tuned here and please contribute on johnreadthepragmaticecologist Facebook site. Questions for 90 year olds

|

Details

John L. Read, PhD, author-ecologistWakefield Press, Dear Grandpa, Why? Reflections From Kokoda to Hiroshima Archives

March 2023

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed